Xi Jinping’s Strategic Choice

Stalin should be praised for his efforts to modernize the Soviet Union, while Khrushchev was too influenced by the West and Gorbachev’s glasnost and perestroika paved the way for the collapse of the Soviet Union. Above all, Putin should be praised for making the Russians proud and patriotic again and for cleansing the country from the poison that made it collapse under Gorbachev. This is the message of a documentary that leading cadres of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are now asked to watch and study as an important lesson for the CCP and for China.

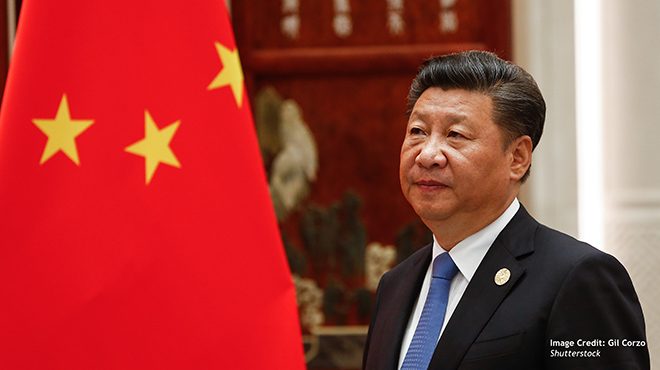

When Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin met in February in connection with the Olympic Games in Beijing, they declared that the friendship between China and Russia has ‘no limits’. The showing of this documentary is one more indication that Xi has made up his mind to bolster this limitless friendship even in the wake of Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, which is causing immeasurable human suffering and threatens the frail stability of the prevailing world order.

Factors behind Xi’s choice to side with Putin

We should see Xi’s choice to side with Putin’s Russia – in spite of official declarations that China will stay neutral – as an expression of one of his major concerns. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, there were speculations that a communist party may not be able to stay in power for much more than seventy years. Apparently Xi early on began to feel and fear this “70-Year Itch”. Preventing the collapse of the CCP one-party rule has the highest priority for him, and in his mind the reform program introduced by Deng Xiaoping after the death of Mao Zedong will just like Gorbachev’s liberalization policies be a deadly threat to this rule, if allowed to go too far. Of course, this perception of the dynamics of the reform program, of “liberalization”, which is the ugly word to refer to it, is by no means new among the Chinese leaders or among the Chinese population. The attempt to carry out the balancing act of promoting economic growth while protecting the CCP Party state has been a major theme for its leaders ever since the introduction in the late 1970s of the program of reform and opening up. In the long run this balancing act may well prove impossible. But it seems that Xi worries more than his predecessors that further reforms and opening-up will lead to the collapse of the Party. Hence the enormous strengthening of Party control over all sectors of Chinese society, unprecedented in the post-Mao era. This suggests that Xi is not content in putting on the breaks but has decided to reverse the course turning backwards in the direction of a new totalitarianism with himself as the all-powerful leader at the helm.

If the perceived threat against continued one-party rule is one of Xi’s main concerns, his perception of the rise of China on the world scene and the approaching demise of the US as the “hegemonic” superpower dominating the world is another of his core ideas. In his view China’s mission is to create a new world order that draws inspiration from traditional Chinese ideas of China being at the center of “all under Heaven”. In this process of a changing world order, the US appears as China’s major rival, not to say enemy. In recent years these two great powers have clashed again and again, and in this international climate, Xi probably finds it natural to form closer ties with Russia, especially since the economically relatively weak Russia poses no threat to Beijing but can supply China with gas and oil at reasonable prices.

No doubt, the most important factor underlying the “friendship without limits” with Russia that has developed under Xi’s rule is the wish to form a united front against China’s main rival and competitor, the US. This policy marks a departure from the rapprochement with the US in the 1970s. At that time Mao and Zhou Enlai identified the Soviet Union as its main enemy and therefore turned to the US. Two decades before that, in 1950, the same leaders, Mao and Zhou, had signed the “Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance”. In this case, too, the driving force behind the close ties with the Soviet Union is the perceived threat from the US.

A relationship of mutual suspicion

In fact, the relationship between the Chinese and Russian communists has been fraught with mutual suspicion ever since the 1920s. After the CCP was founded in 1921, the Soviet and Comintern leaders more than once gave bad advice to their Chinese comrades. Moreover, they took the role of leaders of the world communist movement in a way that evoked the resentment of Mao and other Chinese leader. Nevertheless, power relations in the world – what is now often referred to as geopolitical factors – brought Mao and Stalin close to each other. Now something similar is happening between Xi and Putin.

In addition to the geo-political factors, the fear that the ideas and practices associated with liberal democracy will undermine the autocratic rule of the communist party is also a factor that makes Xi and other leaders in Beijing favor closer relations with Putin’s Russia while defining the liberal democracies as their ideological and political enemies. On top of these factors the seemingly good chemistry between Xi and Putin seems to be one more factor behind this friendship without limits.

Xi’s choice and China’s long-term interests

The factors that we have briefly drawn attention to here can help us see a rationale behind Xi’s choice to support Putin and his horrendous war in Ukraine. But if he continues to defend and even praise him for making Russia patriotic and proud again, the question is if this is really in China’s long-term interest or even good for Xi himself.

China’s phenomenal growth and modernization in the post-Mao era must be attributed to a few causes that we can now identify with pretty great certainty: opening up the country for trade and other forms of exchange with the rest of the world; letting consumer demand, experts and entrepreneurs play a decisive role in achieving economic growth; allowing a more diverse and pluralistic culture; delimiting the role of the party and granting more relative autonomy to government organs and the judiciary. During these more than four decades of modernization, millions and millions of Chinese people have visited other countries, and many have studied in Western countries. Some people have found that Western countries have not lived up to their expectations and we know that nationalism, too often with chauvinistic overtones, is a characteristic feature of contemporary China. As we know it is also a fact that the behavior of many so-called liberal democracies has in many cases left much to be desired. Rather than appearing as models worthy to emulate, Western democracies have on more than one occasion appeared dysfunctional.

Yet, in terms of lifestyle, huge numbers of people in China, especially among the fast-growing middle class, have become very Westernized. Japanese and Western products have a much higher status and are more popular than Chinese products, people like to watch Western movies and TV shows and Western countries are favorites for tourism. Russia on the other hand is associated with poverty and backwardness and failure to modernize. People associate a good life and modernity with countries in the West, not with Russia. Chinese students dream of studying in the US or in Western Europe, not in Russia.

Opposition to Xi’s choice and political course

If relations with the Western world continue to deteriorate and the authorities try to promote more exchange with Russia instead, we can be sure that this will cause resentment among many people in China, probably especially among the middle class who have now acquired the means to travel and to enjoy the benefits that close relations with the Western countries offer.

Among leading cadres and intellectuals, there is still a widespread conviction that continued progress and successful modernization requires more, not less, of reform and opening-up. Not least, this requires continued exchange with the advanced Western countries, in trade, scientific and technological cooperation, and a peaceful international environment. We know that Party veterans associated with former President Jiang Zemin, such as Zhu Rongji, Zeng Qinghong and others, have expressed discontent with Xi’s policies for being detrimental to continued progress. It is hard to believe that Xi’s choice to side with Putin and the deteriorating relations with the US and other Western countries will not breed further discontent. It remains to be seen to what extent this discontent will make Xi Jinping reconsider his choice and political course or affect his position as China’s paramount leader.