Conflict and Climate Change Render UHC Elusive

The objective of providing Universal Health Coverage (UHC) for 1 billion people as set by the Triple Billion target may not to be accomplished by 2025. This estimate is a cause of concern as it indicates that many people still struggle to access quality and affordable primary healthcare. The current context of COVID-19, conflicts, climate change, energy, food, and water resource crises, and political and economic uncertainty have been major barriers to attaining UHC, or the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.8. This is a major issue for people living in fragile and conflict-affected settings (FCAS) where 70 percent of disease outbreaks occur. As December 12 is International Universal Health Coverage Day, deliberating on how to utilize the existing political declaration on UHC to navigate through the current polycrisis situation by building equitable, quality, sustainable, and resilient health systems and moving a step closer to achieving SDG 3, 16, and 17 (health, peace, and partnership) becomes highly relevant.

The challenges faced in FCAS regions such as health infrastructure damage, displacement and migration, supply chain disruption, security risk for health workers, resource scarcity, and increased communicable and non-communicable diseases create a barrier in the implementation of the UHC process. Figure 1 depicts the UHC coverage index of 2021 and highlights the need for actions in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia where FCAS countries are present. Progress towards UHC’s objectives of access to health services, financial protection, and quality services in FCAS countries must begin by strengthening the six building blocks of health systems: service delivery; health workforce; information; medical products, vaccines, and technologies; financing; and leadership and governance (stewardship).

However, the words of WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus that “there cannot be health without peace, and there cannot be peace without health”, highlight the interlinkage of health and peace necessitating a multisectoral approach. While initiatives such as the WHO Global Health for Peace Initiative are already being used as tools to implement the Health for Peace initiative to build sustainable and equitable health systems, various operational and organizational challenges, especially in the FCAS countries, make it difficult to achieve.

Figure 1: UHC Service Coverage Index 2021

Polycrisis in FCAS countries

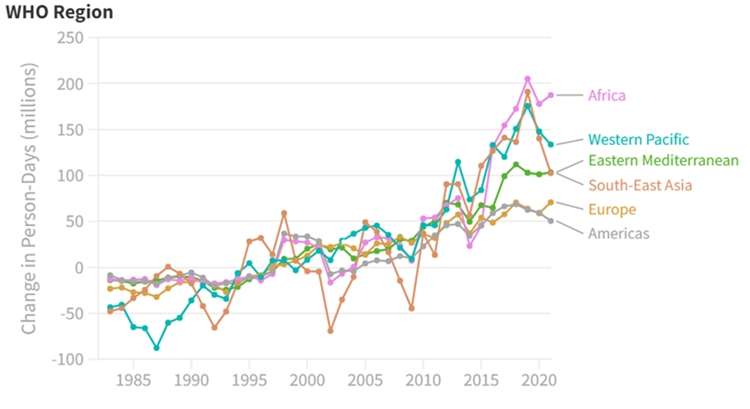

In addition to conflict-induced challenges, the FCAS countries also face the global challenge of climate change. The multisectoral impact of climate change stressors such as heat waves, irregular rains, increased occurrences of disasters, etc., have become key factors in reimagining policy interventions. During the recent COP 28, the health impacts of climate change were put to the forefront of the discussions, which led to 124 countries becoming signatories to the Declaration on Climate and Health. For instance, Figure 2 indicates the exposure of vulnerable population (i.e., infants and people older than 65 in six WHO regions) to heat waves. The increased occurrences of heat waves have increased the transmission of pathogens. Vulnerable populations in WHO regions which have a higher proportion of FCAS countries face a greater threat of heatwave exposure.

Figure 2: Exposure of Vulnerable Populations to Heat Waves

Another major challenge that FCAS countries faced in recent times has been the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite several countries exporting and donating vaccines, many Sub-Saharan countries have the lowest vaccination rates. For instance, even in 2022, several states had not attained a 10 percent immunization threshold, including Yemen, Nigeria, and Senegal among others. Additionally, research revealed there was vaccine hesitancy in close to 30 percent of the conflict zones primarily owing to insecurity, inter-communal conflict, and instability. The concern was mainly associated with fear of side effects and misinformation about the vaccine, leading to 23 and 37 per cent of the population being unwilling to take the vaccines in Somalia and Afghanistan, respectively, despite the deepening crises there.

While international efforts continued to address the COVID-19 pandemic in FCAS countries, world leaders also recognized the importance of preventing, preparing, and responding collectively to any future pandemics by formulating a Pandemic Treaty. However, countries are not yet in agreement due to the lack of accountable measures in place and the geopolitics of global health comprising issues ranging from political and ideological differences to trade and intellectual property rights concerns.

Certainty-Agreement Framework

As FCAS countries continue to experience multifaceted challenges, tackling them would require international agreements and concerted efforts to address the outlined uncertain situations. To navigate critical policy issues like UHC, we can adapt the Stacey Matrix and Cynefin framework of decision-making to the current context as presented in Figure 3. The Stacey Matrix, which depicts the relation between agreement and certainty, suggests that as uncertainty and disagreement increase, the situations become complicated, complex, and chaotic. Whereas in the Cynefin framework, we get an understating of how to react to these different scenarios.

Figure 3 depicts the four main concerns in FCAS countries and their status of agreement and certainty. The situation of conflict has no certainty nor agreement and is the most chaotic scenario to tackle. While there is certainty about the problem of the pandemic, there are still no agreements in place – making it a complicated issue. On the other hand, climate change has several agreements but remains an uncertain situation due to the complexity of the problem. Lastly, with both certainty in action and agreement, UHC is a relatively clear problem to be addressed but needs navigation through the influence of other challenges.

Figure 3: Certainty-Agreement Matrix

To address the concern of UHC, the three other situations of conflict, climate change, and pandemic treaty need to move towards finding certainty and agreement. This could be possible by policymakers’ practicing novel approaches (acting to establish order, sensing the problem and responding) in chaotic scenarios, emergent approaches (probing, sensing and responding to the problem) in complex situations, good approaches (sensing, analyzing and responding) to tackle complicated issues, and best approaches (sensing, categorizing and responding) in case of clear concerns, as recommended by the Cynefin framework.

Adopting a Multisectoral Approach

As UHC is a clear concern with both agreement and certainty, it is essential to point out the challenges it faces, categorize policy options, and respond accordingly. With determinants other than the health sector affecting the accomplishment of UHC, there is a need to incorporate the Health in All Policies (HiAP) initiative that promotes an intersectoral approach to address health concerns. For instance, a collaboration between governments, frontline health workers, and local NGOs aware of the local dynamics played a critical role in enabling a smoother implementation of health service delivery in Honduras. Additionally, as UHC requires redistribution of resources across income and social sections, political factors influence commitment and compliance in implementing government policies. Hence, while formulating health decisions, it becomes imperative to consider the role of interests, ideas, and institutions of other sectors.

When it comes to FCAS countries, the challenge of a triple burden of injuries, communicable diseases, and non-communicable diseases is prevalent. To mitigate this, multilateral platforms such as the G20, G7, and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) can promote collaborative mechanisms focused on strengthening health systems to address the unique challenges posed by these settings. The Indian G20 Presidency, under its theme of ‘One Earth, One Family, One Future’ deliberated on health priorities, including the solutions for aiding UHC. The importance of financing was also emphasized during the Japanese G20 presidency (2019), where the Finance Ministers Communique spoke about how UHC could lead to human capital development which contributes towards sustained and inclusive growth.

While global efforts continue, strengthening national health policies also becomes crucial for FCAS countries. This could be done by adapting existing strategies and models that are effectively in process to achieve UHC. For example, the National Health Insurance (NHI) in Taiwan consolidated the various small insurance schemes into a single national insurance system and played a crucial role in improving public health with a coverage rate of 99 percent. In the case of India, the Ayushman Bharat Yojana comprising two interrelated components – Health and Wellness Centers (HWCs) and Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) – is regarded as the largest scheme in the world, with its aim to provide holistic healthcare delivery.

In addition to this, the Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana (PMBJP) initiated a step towards providing quality medicines at affordable prices. Similarly, examples from Thailand, Cuba, Singapore, South Korea, and the United Kingdom provide multiple strategies and implementation models for efficient policy formulation for UHC at the national level. Therefore, there is a need to utilize such existing international architectures as well as adoption of national strategies that promote a multi-sectoral approach in enabling partnerships and peace for UHC, and reaching every household in FCAS countries.