“Mean China” Turns the Screws on North Korea

China’s ban on coal imports in the latest round of sanctions on North Korea does not equate to it turning its back on its neighbor, argue Eleonora Rossi and Sangsoo Lee.

Last month was a busy period for North Korea watchers.

On February 12, Pyongyang successfully conducted its first missile test of 2017, and on the following day, Kim Jong Un’s elder brother, Kim Jong Nam, was allegedly assassinated (though this remains vehemently denied by Pyongyang) at Kuala Lumpur airport. Just a week later, on February 19, China announced a ban on coal imports from North Korea.

In response to the ban, North Korea harshly criticized the “mean behavior” of China, KCNA News charging it as “a neighboring country which often claims itself to be a ‘friendly neighbor’ … while dancing to the tune of the U.S.”

While China has previously imposed embargoes against North Korea, the latest coal import ban is by far the toughest measure enacted by Beijing. But, should it be considered as their turning point for a more hardline stance towards the DPRK?

China’s Coal Ban

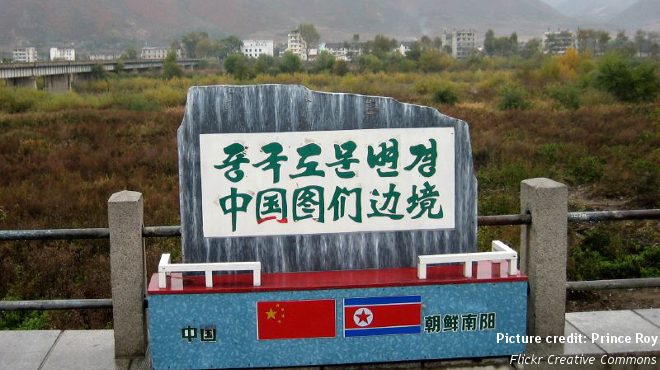

North Korea is dependent on China for almost 90 percent of its external trade and coal is estimated to account for 40 percent of North Korea’s exports to China. In 2016, North Korea ranked as China’s biggest supplier of high-grade anthracite coal, used mainly by the country’s steel mills.

China’s announcement of a total coal import ban through to the end of 2017 – if enforced – is likely to catalyze a decline in North Korea’s economy this year. The value of this suspension could reach $1 billion, amounting to a 3 percent reduction in North Korea’s GDP; but the actual economic damage would likely be greater because China is one of North Korea’s few sources of hard currency.

The Chinese Ministry of Commerce claimed the coal ban had been enacted to comply with last November’s United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2321, following North Korea’s fifth nuclear test. The resolution stipulated a quota for coal exports not exceeding $53 million or 1 million tons by December 31, and a quota for coal exports not exceeding $400 million or 7.5 million tons through the end of 2017.

Loopholes in Sanctions

Despite China’s announcement, the impact of the coal ban relies on its full implementation. Exploiting a loophole in Resolution 2321 under an “exception clause,” in December 2016 Beijing imported three times the permitted amount of coal.

Furthermore, a UNSC Report from last February revealed that North Korea is “flouting sanctions through trade in prohibited goods, with evasion techniques that are increasing in scale, scope and sophistication.”

Although the customs clearance process is reported to have been strengthened, there is evidence that coal trading has continued in Rizao Port, Shandong Province, where controls are regarded as relatively lax.

According to Daily NK, the majority of the illicit coal trade occurs between individual merchants. Even if regulations are strengthened, merchants can still forge documents to record coal imports as “other goods,” or can loan vessels registered in other countries.

Two-track Approach

Whilst the coal ban illustrates Beijing’s displeasure with Pyongyang its implementation is unlikely to be too strict. As long as Beijing does not take further action to punish Pyongyang, the coal ban in itself is not the strongest card among Beijing’s tools of leverage. More serious, for instance, would be a long-term ban on oil supplies which could severely undermine the regime’s stability.

Despite the sanctions and the harsh exchange of rhetoric between the two countries, on February 28 the North Korean Vice Foreign Minister, Ri Kil Song, arrived in Beijing at the invitation of the Chinese Foreign Minister, Wang Yi. During his five-day visit he met with a number of senior Chinese officials.

An editorial in the state-controlled Global Times of China maintained that in spite of the coal import ban, China’s friendship with North Korea will “remain unchanged.”

The visit evidences China’s two-track approach – one of tougher economic sanctions but also maintaining political support to North Korea. While China wants to see Pyongyang cease its nuclear and ballistic missile program, and through selective sanctions is prepared to apply pressure, its punitive actions are carefully weighted so as not to endanger the stability of the regime itself.

Furthermore, the ban may also serve the purpose of demonstrating China’s responsiveness to external, namely U.S., pressure to take action. With the Trump administration reviewing all options, from dialogue to preemptive strikes, to forge a new policy vis-à-vis North Korea, Beijing is eager for Washington to take the initiative on returning to the negotiating table. This requires both sides to find a modicum of common ground to coordinate talks.

Indeed, on February 17, the Chinese foreign ministry expressed hopes for the resumption of the long moribund Six-Party Talks, a clear signal that it sees dialogue – and ultimately not coal bans or other sanctions – as the only viable path to deal with North Korea.

Eleonora Rossi is completing an internship at ISDP. Sangsoo Lee is Senior Research Fellow at the Institute.