From Silos to Synergy: Harmonizing Global Actions for Biological Diversity

Introduction

“Without nature, we have nothing” was a resounding statement made by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres at the Conference of the Parties (COP) 15 in 2022, highlighting the importance of alignment of human development with biodiversity conservation. At the same event, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) was adopted, which set 23 targets and four overarching goals of i) Maintaining, enhancing, and restoring ecosystems and species; ii) Sustainable use and management of biodiversity; iii) Fair and equitable sharing of benefits; and iv) Adequate means of implementationfor 2030. This new framework was introduced after learning from the shortcomings of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets due to its vague metrics, insufficient financing, and limited accountability–out of the 20 targets, only six were partially achieved, 13 of them had no progress, and the rest had uncertain outcomes. One of the major reasons for the lack of the effectiveness was the policy fragmentation manifested in poorly aligned, inconsistently implemented national strategies and a lack of cross-sectoral coordination. Thus, there is a need for synergy in the global action towards biodiversity conservation.

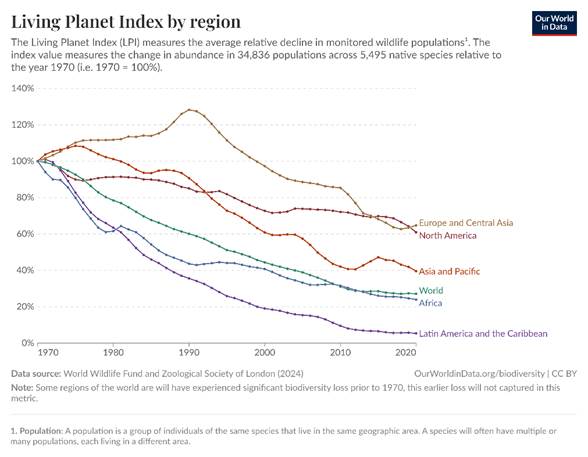

Every year on May 22, the International Day for Biological Diversity is observed to commemorate the adoption of the text of the Convention on Biological Diversity (May 22, 1992) and to foster wider support for its implementation. This year’s theme of “Harmony with Nature and Sustainable Development” offers an important reminder that economic growth and human well-being are deeply dependent on thriving ecosystems. Harmonious interactions between humans, animals, and the environment are critical to the growth and development of biodiversity. However, there is an unprecedented level of threat to biodiversity driven by land use change (deforestation, agriculture, urbanization, over-exploitation of resources, pollution, invasive species, and climate change. According to the Living Planet Index (LPI), there has been a 73% decline in wildlife populations globally over the past 50 years (1970–2020). Figure 1 suggests that the LPI in Latin America and the Caribbean has seen the steepest regional decline in wildlife population at 95%, with Africa at 76% and Asia-Pacific at 60%. Additionally, over 41,000 animal species are threatened with extinction, including 41% of amphibians, 33% of reef-forming corals, 27% of mammals, and 13% of bird species. The estimated impact on the global economy from the loss of biodiversity is more than USD 5 trillion a year. These alarming figures indicated not just an ecological crisis but also economic stability, food security, planetary health, and human well-being.

Figure 1: Living Planet Index

Source: Living Planet Index – Our World Data (Living Planet Report 2024)

One of the major impacts of the loss of biodiversity is on human health and well-being. In recent years, there has been an increases in the outbreaks of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases such as Rift Valley fever, Ebola, SARS, H1N1, Yellow fever, Avian Influenza (H5N1) and (H7N9), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), Zika, COVID- 19, and Mpox. Over 60 percent of new human pathogens have originated from animals (zoonoses). Such zoonotic diseases are estimated to cause 2.5 billion human illness cases and 2.7 million deaths annually across the world. The preservation and enhancement of biodiversity, especially of small mammals, higher vertebrates, and habitat, can enable effective prevention of these deadly zoonotic diseases. This necessitates a united, holistic, and cross-sectoral strategic action using the One Health approach that breaks silos and advocates for the interconnectedness and interdependence between human, animal, and environmental policies. However, in order to realize such a strategic action for biodiversity conservation, there is a need for harmonization of the global governance structure, policies, and political will for effective outcomes.

Global Action for Biodiversity Conservation

Global action towards biodiversity conservation has been a continuous process with multiple international organizations, conventions, treaties, and resolutions being passed (see Table 1). The landmark 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) opened at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Earth Summit) in Rio de Janeiro, established a global framework for biodiversity conservation, sustainable use of resources, and equitable benefit sharing. Organizations like International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) have been critical in enhancing funding, promoting evidence-based coordinated policy making to conserve biodiversity and enable sustainable development.

Table 1: Biodiversity-related conventions

| Name of the Conventions and Resolutions | Focus |

| Convention on Biological Diversity | Biodiversity conservation, sustainable use of resources, and equitable benefit sharing |

| Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) | Global trade of specimens of wild animals and plants |

| Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals | Conserve terrestrial, marine and avian migratory species |

| The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture | Conservation and sustainable use of plant genetic resources for agriculture and food security |

| Ramsar Convention | Framework for sustainable use of wetlands and resources |

| World Heritage Convention (WHC) | Conserve cultural and natural heritage |

| International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) | Protection for plant resources and preventing spread of plant pests |

| International Whaling Commission (IWC) | Conservation of whale stocks |

| UN Resolution 64/203 (2009) and Resolution 65/161 (2010) | CBD as a key tool for biodiversity conservationNational action plans and ratification of CBD2011-2020 as United Nations Decade on Biodiversity |

| UN Resolution 76/207 (2021) and 77/167 (2022). | Enhanced cooperation Integrating climate change adaptation and mitigation efforts, disaster risk reduction, and sustainable development |

| UN Resolution 78/155 (2023) | Implementation of the CBD with nature-based solutions and ecosystem-based approaches Importance of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge |

While there have been several global commitments, these multiple overlapping international frameworks and conventions (e.g., CBD, Ramsar, CITES) often operate in silos, leading to inefficiencies and conflicting priorities. For instance the Pacific Island countries faced heavy administrative and resource burden due to duplication of reporting until a consolidated reporting template was formulated with the assistance of Australian Government. The differing legal frameworks and priorities of the CBD and CITES could lead to policy divergence, as CBD’s access and benefit-sharing provisions may conflict with international intellectual property regimes and complicate national implementation. Additionally, international treaties in climate change, trade, agriculture, wetlands, migratory species, and land management sectors all intersect with biodiversity conservation. They influence biodiversity both directly (e.g., regulating trade in endangered species) and indirectly (e.g., shaping land use, climate policies, and resource exploitation). Thus, harmonization of these treaties, conventions, and regulations, becomes imperative for effective biodiversity conservation.

The developing countries face unique challenges in both the planning and implementation of addressing concerns of biodiversity. Despite being biodiversity-rich, they often suffer from inadequate and unsustainable funding to scale successful projects. A lack of reliable, harmonized, and accessible biodiversity data impedes sound policy design, monitoring, and adaptive management. Policy fragmentation and isolation between the ministries of health, agriculture, and environment weaken the ability for coordinated responses.

Despite these challenges, the adaptation of these global commitments to national strategies have enabled progress in biodiversity conservation have become extremely important to address the concern of the zoonotic diseases. For instance Schistosomiasis, a major waterborne zoonotic disease that affected millions in Sub-Saharan Africa, mainly emerged due to the disruption of natural river ecosystems by large-scale dam construction and river modification. However, introducing native river prawns that preyed on the intermediate host of pathogen reduced the transmission of the disease and increased the biodiversity resilience. Another interesting case is from the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, where to combat coral bleaching and degradation due to rising temperatures and climate change, it has been identified that decommissioned sunken ships could be used to strategically placed to create artificial reefs to enhance biodiversity and reduce pressure on natural reefs. There is a need for policy diffusion of such ecosystem-based interventions across countries and regions where zoonotic diseases are emerging due to human activities and environmental degradation.

Way Forward

The One Health approach plays a pivotal role in preserving biodiversity and reducing disease risks by integrating efforts across sectors to promote sustainable balance of health of people, animals, and the environment. By integrating efforts across sectors, encouraging sustainable management of natural resources, and promoting community participation and inclusion of traditional knowledge practices becomes critical in the equitable benefit sharing of biodiversity conservation using the One Health approach. The resulting natural barriers makes it harder for pathogens of zoonotic diseases to spread and reduces likelihood its outbreaks. As the One Health approach brings emphasizes the collaboration of experts across human, animal and environmental sector, integrated disease surveillance can be vital for early detection and rapid response.

At national level, development plans across sectors need to incorporate the One Health approach in design, development, and deployment. For effective outcomes, there is a need for alignment and integrated planning mechanism of policy objectives of biodiversity, health, agriculture, climate, infrastructure, and foreign policy. The inter-ministerial task forces, cross-cutting budget allocations, and unified monitoring systems would be essential in mainstream biodiversity into broader national priorities. Integration of Ecological or Biodiversity Corridors in development plans for facilitating ease of movement for migratory animals and birds could be promoted. Utilization of biodiversity modelling systems like the GLOBIO framework could provide support for policy making, support international negotiations, track progress towards biodiversity targets, and aid in the valuation of ecosystem services essential for human well-being.

Investing in collaborative research and development of satellite-based surveillance technologies and AI-based predictive models can enable real-time monitoring, prepare for future calamities, and evidence-informed policy making. Incentivising private players and philanthropies to provide funds for scaling successful biodiversity projects through green tax and subsidies, blended financing models, global certification and awards for contribution, creating coalitions of private players, and providing long-term revenue schemes can be considered. With the world being confronted with interconnected challenges of climate change, pandemics, and ecological collapse, the One Health approach that offers a fundamental shift in how policies develop and are implemented must move from fragmentation to integration. The cohesive, cross-sectoral, and collaborative guided by evidence and science are essential to achieve harmony with nature and sustainable future.