First Fiji, Then the World

Larissa Stünkel and Grant Wyeth

How the prime minister of a tiny group of Pacific islands has become an international power player.

See original article in Foreign Policy here.

Immediately after his election victory in November, Joe Biden received an ambitious invitation. Fiji’s Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama wasn’t wasting any time; he wasn’t concerned with the former president’s attempts to overturn the election, and he certainly wasn’t going to wait until the transfer of power was complete. Fiji is due to host the annual Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) this August, and Bainimarama desperately wants Biden there. After four years where the world’s most powerful person had disparaged and neglected the Pacific Islands’ most pressing issue—climate change—the ear of his replacement was now deemed essential.

There was a time when Pacific Island leaders would have considered making such a request above their station. Traditionally reserved and unassuming, they would have instead seen the path for advancing their interests as running through PIF heavyweights Australia and New Zealand. Yet with Australia’s continued recalcitrance towards climate change creating significant friction at the most recent in-person PIF meeting, Bainimarama has been compelled to try a different tactic, one that could go over Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s head, and restrain him from producing a repeat performance. The presence of a U.S. president who took climate change seriously would, therefore, do the trick nicely.

This inclination to seek creative solutions to Fiji’s problems has been Bainimarama’s defining feature over the past two decades. He is a man who bristles at constraints—whether they be democratic or geopolitical—which has not endeared him to many both domestically and internationally. Yet through sheer force of personality, a great deal of cunning, and some lucky global trends, Bainimarama has been able to gain an outsized international influence for Fiji that exceeds its reality as a group of geographically isolated islands of less than a million people.

Bainimarama came to political prominence in the aftermath of the semi-successful coup against Fiji’s first Indo-Fijian prime minister, Mahendra Chaudhry, in 2000. A militia formed by businessman and Indigenous Fijian nationalist, George Speight, stormed the parliament building in the capital Suva and held Chaudhry and most of his cabinet hostage for 56 days. With Fiji’s mostly ceremonial president unable to seize control of the situation, Bainimarama, as the commander of Fiji’s armed forces, declared martial law, arrested Speight, and assigned himself the head of an interim military government. A month later he appointed a new civilian government, this time led by Indigenous-Fijian Laisenia Qarase.

Maintaining his position as the head of the military, by 2006 Bainimarama had grown disillusioned with Qarase’s government. Allegations of blatant misappropriation of government funds were the stated source of Bainimarama’s discontent, yet since the events of 2000 he had also been developing his own ideas on how to resolve the negative power dynamics between the country’s two main ethnic groups. Qarase’s attempt to pass legislation to provide amnesty for Speight and his militia turned out to be the final straw. Bainimarama struck, enforcing Fiji’s fourth coup in over 20 years. This time, however, he himself would assume the role of prime minister.

His primary conviction to “clean up” the government initially earned him much support, especially within the Indo-Fijian community. Although, ironically, one of Bainimarama’s first acts was to grant amnesty to all those involved in his own coup. Yet, continued divisions within the Indigenous Fijian-dominated military over Bainimarama’s vision for the country led to a failed plot to assassinate him in 2007. Coupled with this, external pressure from regional powers Australia and New Zealand to restore democracy became fierce. Bainimarama nonetheless felt he had serious work to do in reforming Fiji’s political institutions, and this would take time. A promise to restore democracy in 2009 came and went, and eventually resulted in the Pacific nation being suspended from the PIF.

Eventually, in 2013, he delivered a new constitution, one that he hoped would counteract the country’s internal divisions. It eliminated race-based electoral rolls and ethnic seat quotas, while abolishing both the parliament’s unelected upper house and the powerful Great Council of Chiefs. These changes were intended to remove the structural privileges that Indigenous Fijians held within the country’s political institutions and signaled an attempt to neutralize perpetual domestic ethnic divisions. Since then, the new constitution simply refers to all Fiji citizens as “Fijians”, and only a recognition of iTaukei and Hindi—alongside English—as the country’s official languages acknowledges the country’s ethnic make-up.

However, with the democratic process in Fiji postponed, Bainimarama’s image as a power-hungry coup leader increasingly marginalized the country in the region. The suspension from PIF had prevented Fiji from having its interests considered within the Pacific’s primary multilateral body, and Bainimarama was ostracized by both Canberra and Wellington. When Fiji was readmitted to PIF in 2014, and still holding a grudge, Bainimarama snubbed the other forum members by sending lower-level officials. Only making an in-person appearance in 2019.

Bainimarama felt that his powerful neighbors were failing to understand what he sought to achieve with his sweeping reforms. He believed that his 2006 coup and eight-year suspension of democracy were necessary actions to reconstitute the country in a manner that would, once and for all, overcome its deep-rooted ethnic divisions. However, Bainimarama’s avowed reforms failed to extend into Fiji’s most powerful institution—the armed forces, which remains almost exclusively Indigenous Fijian, partially due to its close relationship with the socially dominant Methodist Church.

In hindsight, rather than forcing Bainimarama into submission, Fiji’s suspension from PIF inadvertently emboldened him to craft a more assertive foreign policy, one aimed at circumventing Canberra and Wellington. Besides seeking to establish Fiji as the Pacific’s central regional voice, he also promoted the rebranding of Pacific Islands as “large ocean states” rather than small island developing states. Additionally, he forged an ambitious “Look North” policy to broaden Fiji’s diplomatic reach, with greater south-south cooperation and stronger links with emerging powers. Although refusing to attend PIF, from the outside Bainimarama stressed that the agenda of the body should be set by Pacific Island states, and not by Australia and New Zealand. Not content with their pompousness, Bainimarama led the creation of the Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF), a No-Homers Club that unequivocally excluded the Pacific’s resident powers.

Unconcerned with the state of Fiji’s democracy, the post-coup environment provided an ideal window of opportunity for China to step up its presence in the Pacific, something Bainimarama enthusiastically embraced. Russia also sensed an opportunity with a “donation” of arms, a cohort of military advisers, and a high-profile visit from Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. In addition, Bainimarama sought to generate stronger links with Indonesia, as it tried to establish its own Pacific identity. Although this created tensions within the Melanesian Spearhead Group, where several members are strong supporters of West Papuan independence and who felt the Fijian leader was being groomed by Jakarta in order to sow divisions within the sub-regional grouping.

These attempts to diversify Fiji’s strategic partners was starting to set off alarm bells in Canberra. Australia’s primary security objective is to prevent unaligned powers from gaining military access to any Pacific Islands, which could—theoretically—be used as an advance base to either attack Australia or limit its ability to maneuver. China’s growing interest and assertiveness in securing access to maritime resources, coupled with its increased footprint in the Pacific—including poaching two of Taiwan’s allies in the region in 2019– was deemed a significant threat to Canberra’s objective.

This anxiety about Chinese activity in the region led to both Australia and New Zealand hurriedly creating reengagement policies—Canberra’s Pacific Step-Up and Wellington’s Pacific Reset—that were intended to work in tandem to maintain their regional hegemony. With Bainimarama having successfully positioned himself as the lynchpin and strategic organizer of the island nations—and by 2018 having won two democratic elections, legitimizing his support in Fiji—Australia and New Zealand now felt compelled to bring him in from the cold.

In 2019 Morrison made two trips to Suva to reconnect with the Fijian leader, while also hosting him in Canberra the same year. There, the Fijian leader received a ceremonial welcome, with a military guard of honor, a 21-gun salute, and all the trappings of a fêted and powerful world leader, signaling an extraordinary transformation of his status in the Australian capital. While in Canberra, he signed a new strategic cooperation agreement—the Fiji-Australia Vuvale Partnership (vuvale meaning family in iTaukei). The concept being that families can have disagreements, but they are bonded by connections that can transcend such disputes.

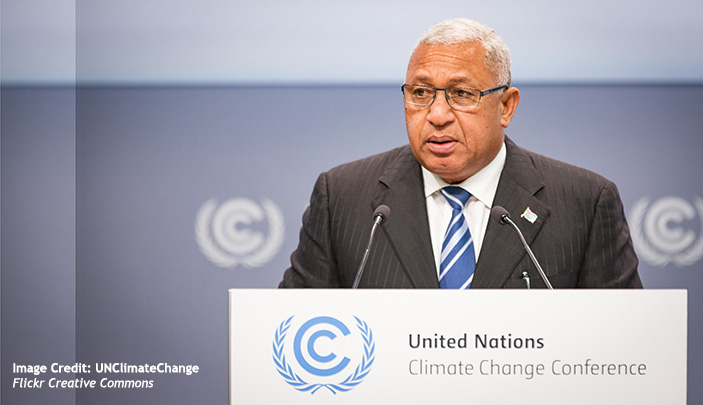

Apart from reshaping the region’s geopolitical playing field in Fiji’s favor, Bainimarama’s expanded influence afforded him the opportunity to fiercely advocate for significant action on climate change. After all, Pacific Island states make negligible contributions to the world’s carbon emissions yet are disproportionately affected by the environmental consequences. For many low-lying Pacific islands, the threat from climate change make them the canaries in the coalmine. In recognition of this, Fiji held the presidency of the United Nations Climate Change Conference 2017 to 2018 (COP23), with Bainimarama issuing a stern warning that no one “will ultimately escape the impact of climate change.”

Reemerging at PIF’s 2019 meeting in Tuvalu, Bainimarama targeted Morrison for Australia’s climate change complacency, highlighting how Australia’s concurrent domestic energy policy contradicted Canberra’s efforts to be an engaged and helpful partner to Pacific Island countries. In particular, he made it clear that Australia’s enormous coal industry had become an existential threat to the region’s low-lying atolls. Seizing on Morrison’s subsequent defensiveness and derogatory remarks, Bainimarama tactically singled out Canberra’s patronizing and self-satisfied behavior as being a key reason for Pacific countries to turn to China for support.

While this also played into the hands of Beijing, the move allowed Bainimarama to reframe the narrative of climate change action as a national security concern for Australia, using China’s Pacific presence as a bargaining chip to reengage with Canberra on his terms. Although, ironically, China produces and uses far more coal than Australia, somewhat undermining Bainimarama’s tactics, this should be considered immaterial to Canberra’s own obligations.

With PIF now facing a legitimacy crisis after five Micronesian states signaled their intent to withdraw from the body, Bainimarama’s quest to present a unified Pacific voice to the world has suffered a significant setback. As three of these Micronesian countries are in compacts of free association with the United States, Bainimarama’s desire to have Biden physically present in Suva in August may now be needed not only to highlight the Pacific’s environmental concerns and place pressure on Morrison. In addition, it could serve to mend the very body that once shunned the Fijian leader. Convincing Biden to attend the summit may therefore end up being Bainimarama’s most consequential coup yet.

Related Publications

-

Navigating the Indo-Pacific: How Australia and the EU Can Partner for Peace, Stability, and Prosperity

To navigate the choppy waters of the Indo-Pacific, the EU and Australia must be on the same wavelength regarding shared interests in rules, values, and an open and liberal economic […]

-

“Yizhou 夷洲” and “Liuqiu 流求” in Historical Chinese Texts: International Relations on the Northeast Asian Seas (3rd-17th Centuries)

Sun Quan 孫權, Emperor Da of the Eastern Wu, and Emperor Yang of Sui Yang Guang 楊廣 sent armies across the sea to invade Yizhou and Liuqiu between the 3rd […]

-

Russia is a systemic threat and Europe must wake up to face it

While travelling in Europe lately, it has become clear there are a couple of widespread beliefs that do not accurately capture the essence of the Russian challenge after its war […]

-

First Stockholm Forum on Himalaya calls for Greater Collaboration between India, the EU & the US

China’s role as a revisionist power in the region needs to be addressed Urgency of tackling both environmental and geopolitical issues in the Himalayas October 17, 2024: The first-ever Stockholm […]

-

The US and EU, and the Emerging Supply Chain Network: Politics, Prospects, and Allies

The Global Supply Chains have evolved from simply logistical achievements to being the bedrock of the global economy. Driven by technological advances and geopolitical shifts, this transformation underscores the critical […]