Strategic Duality: India and China in the EU’s Connectivity Agenda

Jagannath Panda

The European Union (EU) frames its Global Gateway Strategy (GGS) as a rules-based initiative to enhance global connectivity, pledging around EUR 300 billion through 2027 to develop “smart, clean, and secure” infrastructure that aligns with EU standards. Brussels presents the GGS as a model for “equal partnerships” in infrastructure and digital development, emphasising democratic governance, strong environmental and social safeguards, and transparency. This framework positions India and China very differently. India is considered a like-minded partner, while China is implicitly regarded as a strategic rival—albeit one with indispensable economic significance.

These divergent perspectives pose the central question of this piece: How is the EU’s GGS positioning India and China, and what do their differing reactions imply for the EU’s broader connectivity ambitions? And what do India’s and China’s responses tell us about the viability of Europe’s strategy?

Duality in EU Perspective

EU–India statements underscore New Delhi’s role as a key partner in the Indo-Pacific. EU President von der Leyen described India as a “leading voice of the Global South” and a “bridge” between Europe and the Global South. In June 2025, India’s External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar and European Commissioner for International Partnerships Jozef Síkela reaffirmed their commitment under GGS, emphasising “investing together in sustainable development projects that create jobs, connect communities, and strengthen our global resilience.” These projects are specifically chosen to reflect shared values.

While India remains a like-minded partner for much of Europe, it has not yet emerged as a preferential one. India has to work hard at building confidence, especially in the wake of its stance on Russia. Although Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s well-known declaration that “this is not an era of war” had resonated in parts of Europe, policymakers remain wary of India’s continued energy imports from Moscow. Many continue to perceive India as leaning toward Russia—a stance some interpret as implicitly opposing Ukraine, and by extension, Europe. For a continent rallying behind Ukraine, this perceived ambiguity has made full political trust elusive.

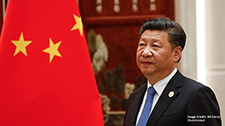

The EU–China relationship, meanwhile, stands at a pivotal juncture, as commemorated by the 50th anniversary EU–China Summit in Beijing on July 24, 2025. While diplomatic lines remain open, structural mistrust over trade and security casts a long shadow, making any substantial breakthroughs elusive in the near term. The EU is pursuing a policy of “de‑risking, not decoupling”, aiming to safeguard critical supply chains and diversify dependencies while staying engaged across climate, energy, tech, and regulatory dialogues.

Since its launch in 2021, the GGS has often been billed as a values-based, high-standard alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). GGS pledges to uphold open procurement and high environmental and social criteria—features that distinguish it from the BRI, whose contracts often favours China’s state-owned enterprises and financial institutions. The initiative appears designed to address critiques commonly associated with the BRI, including unsustainable debt burdens and limited developmental spillovers. Though China features rarely —if at all—in the official rhetoric on the GGS, its presence is implied. This has inevitably shaped China’s view of the initiative as a geo-strategic gambit of the EU. While Brussels sees GGS as a vehicle to “tackle pressing global challenges” and promote EU norms, a leaked EU strategy document goes further to describe GGS as a tool in a geopolitical “battle of offers” with China.

In short, the EU has positioned India as a strategic ally in building resilient, rules-based connectivity, whereas China has been implicitly framed as the competitor whose model GGS is meant to counter. This duality has elicited markedly different responses from India and China.

China’s Strategic Response

China’s state media have been quick to dismiss the GGS, along with similar initiatives like the India–Middle East–Europe Corridor (IMEC). They portray GGS as “another rubber check” from the West, which lacks “credibility” and is subtly framed as attempts to counter the BRI. These commentaries openly question the strategic viability of the Global Gateway, arguing that such projects “will never be taken seriously” unless Brussels abandons what they describe as a narrow, agenda-driven approach. They further highlight EU’s constraints—ranging from war-induced fiscal deficits to growing debt fatigue—arguing that the EU’s funding for GGS is both limited and heavily conditional.

Despite the critical tone, Chinese diplomats have not missed opportunities to call for interaction between the BRI with the GGS. Some state media outlets have even suggested that the GGS should “join hands” with the BRI, rather than position itself as an alternative.

This blend of critique and outreach reflects China’s strategic ambivalence. Such ambivalence stems from China’s perception of the EU as a normative power leveraging connectivity to assert influence and shape global standards. At the same time, Beijing also regards the EU as a major geopolitical player whose partnership remains strategically important. Since 2023, however, Beijing has stepped up diplomatic efforts to frame itself as “willing to synergise” its BRI with the GGS. In 2025, Foreign Minister Wang Yi reinforced this overture, proposing to “leverage” the respective strengths of China and the EU.

India’s Engagement with the EU

New Delhi has largely welcomed closer EU ties as complementary to its own Indo-Pacific outreach. Europe notes India’s active engagement in joint GGS connectivity projects (in green energy, digital infrastructure, etc.) to diversify supply chains and develop third-country connectivity in line with a “shared” vision of connectivity across Europe, Asia, and the world. India’s strategic significance to the EU’s GGS further lies not only in its pivotal geopolitical and economic role, but in its ability to either legitimise or constrain the EU’s attempt to provide a credible alternative to China’s BRI.

Despite many fundamental differences between India and the EU on normative principles, New Delhi sees the EU as a like-minded partner in countering infrastructure and technology strategies that threaten Indian sovereign and security interests—most notably the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a BRI project. Hence, India’s stance on Global Gateway is more positive, even if cautious. Jaishankar called it a “step in the right direction.” Further, arguments for GGS to become a defining factor of India–EU ties have shaped engagements with the normative idea of the strategy. Crucially, both the GGS and the EU–India Connectivity Partnership were launched in 2021, marking the start of an institutionalised approach to connectivity and laying the foundation of strategic alignment. In February 2023, the two sides launched the India-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC)—only the second such EU forum, the first being with the US—to coordinate on digital, energy, and supply-chain issues. This further strengthens the complementarity between India and the GGS on digital public infrastructure projects. In practice, this will enable India to pair its world-class digital platforms, such as unified payments and open-data networks, with EU funding for projects in Africa and Asia. This aligns with India’s efforts to position itself as a partner to developing economies.

Amidst escalating China-EU trade rifts, the positive progress of the India-EU Free Trade Agreement (FTA) negotiations—pledged by both sides to be expedited by 2025—alongside plans to use the IMEC as a testbed for connectivity, is interpreted in Delhi as evidence of Brussels’ intent to elevate EU-India strategic partnership.

EU’s Global South Calculus: India and China

Having become the top trading partner for over 120 countries in 2023, China continues to hold more sway than the EU and India in many Global South markets. From Asia to Latin America and Africa, Chinese companies consistently outcompete Western counterparts on both price and scale. For instance, China has maintained the top trading partner of Africa for sixteen years. Such outpacing of the EU and India across the developing world calls for an urgent review of both Brussels’ and Delhi’s game plans. In essence, Brussels now treats India as an emerging “pole” in the Global South that competes with China for influence in the same strategic space.

Under the EU’s strategic discourse, China is largely viewed as a systemic rival. Terms such as “strategic autonomy” and “de-risking” frequently appear in Brussels’ narratives to Beijing, reflecting caution and concern. India, by contrast, is portrayed as a partner and an emerging leader of the Global South. However, India’s global influence remains relatively modest. Currently, it is not a major lender like China and lacks large-scale, state-backed soft-power institutions operating in Africa or Asia.

Comparatively, in the EU’s calculus, India’s advantage lies not in the economy of scale but in strategic alignment. Its democratic system, sizeable market, and pivotal geographic location in the Indo-Pacific suit Europe’s vision of a rules-based international order. As a result, Brussels is increasingly orienting its Global South strategy around deeper collaboration with India. The EU appears to hope that by working with India, it can present an alternative model of development—one that respects sovereignty, human rights, and financial sustainability— which it positions as distinct from the BRI. Meanwhile, Brussels must reconcile with India’s foreign policy stance on issues like Ukraine while also navigating the reality that Beijing remains an essential economic partner.

This piece was first published in China-India Brief (no. 257, July 01, 2025 – July 31, 2025), a publication outlet of the Centre on Asia and Globalisation, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore.