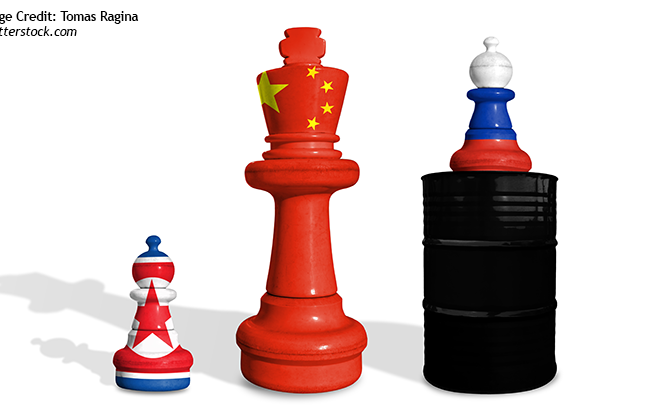

Reading North Korea: Russia and China as Case Studies

North Korea-Russia relations have faced renewed international scrutiny since September 2022, when Pyongyang was first reported to be supplying artillery shells and rockets to Russia. The institutionalization of bilateral relations following Kim Jong Un’s September 2023 summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin, the June 2024 signing of the North Korea-Russia Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, and North Korea’s reported initial dispatch of troops to Russia in October 2024 – officially confirmed by both countries six months later – have fueled debate over whether the relationship will outlast the Russo-Ukraine war or represents a longer term, strategic alignment.

Meanwhile, North Korea’s ties with China, overshadowed by its burgeoning relations with Moscow, catapulted back to international headlines in recent months. After nearly two years of strained relations, the two countries resumed high-level exchanges beginning with Kim’s highly publicized September visit to Beijing for China’s “Victory Day” celebrations, followed by China’s dispatch of a high-level delegation to a North Korean military parade in October. Despite some assessments that Pyongyang-Beijing relations have entered a “new era,” North Korea’s intentions toward China may be less straightforward than headlines suggest and require continued analysis.

The key to understanding North Korea’s current and future thinking on key policy issues, including its relations with Russia and China, is how they are portrayed in state propaganda. This essay assesses North Korea’s relations with Russia and China, and their likely trajectory, by analyzing how state media have handled these two countries in 2025.

The Case for Propaganda Analysis

Before we jump into Pyongyang’s relations with Russia and China, the research methodology on which this paper is based – propaganda analysis – may be worth a brief mention. There are two common (and related) questions regarding North Korean propaganda analysis: Why should we place any weight on what North Korea says, as it is all state controlled anyway? Also, are they not all lies?

North Korean media matter precisely because the regime exercises complete control over them to shape and manage domestic and international opinion. Pyongyang, therefore, is extremely deliberate in its public messaging: what information it releases and how it frames that information, at what level, to whom, and when. As such, by tracking patterns and shifts in North Korea’s public messaging, one can gain insight into the leadership’s current and future intentions toward any issue.

Pyongyang-Moscow Relations: Looking Beyond the War in Ukraine

North Korea has made consistent efforts to institutionalize bilateral exchange and cooperation with Russia across all sectors and levels following Kim Jong Un’s summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin in September 2023 and the June 2024 North Korea-Russia Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.

Of particular note is the regular high-level coordination between the two countries, exemplified by the annual strategic dialogue between the North Korean and Russian foreign ministers, and frequent visits to North Korea by Sergei Shoigu, secretary of the Security Council and a known confidant of Putin. Pyongyang’s April 2025 acknowledgement of troop deployment to Kursk, which followed Russia’s announcement two days before, and its meek Foreign Ministry statements on the Israel-Iran conflict in June, issued shortly after Kim’s meeting with Shoigu, pointed to how closely the two countries choreograph public messaging on key international issues.

The evolution of North Korean media’s language describing the bilateral relationship is also worth noting. Following the September 2023 Putin-Kim summit, the Workers Party of Korea (WPK) for the first time said North Korea-Russia relations had “independence against imperialism as an ideological basis,” effectively giving the relationship an ideological underpinning similar to North Korea-China relations. Reporting on the signing of the new treaty in 2024, North Korean media cited Kim Jong Un as describing the bilateral relations as an “alliance.” Since North Korea’s public acknowledgement of its troop dispatch, this formulation has been upgraded to a blood-forged alliance.

North Korea’s positive media coverage of the Kim-Putin talks held on the sidelines of China’s “Victory Day” celebrations in September was consistent with trends over the past two years. In October, Russia’s ruling United Russia Party (URP) and the WPK issued an unprecedented “joint statement” where Russia expressed “firm support” for North Korea’s defense buildup, presumably including its nuclear programs. Later that month, North Korea’s official report on the North Korean and Russian foreign ministers’ talks stipulated that Russia expressed “full support” for Pyongyang’s efforts to defend “the state’s present position [국가의 현 지위; kukka-ui hyon chiwi],” which appeared to refer to North Korea’s self-declared nuclear status.

The trends over the past two years reflect Pyongyang’s commitment to a longer-term relationship. North Korea has reported that Kim and Putin have started to discuss “in detail the long-term plans for cooperation between the two countries,” indicating top-level discussions during an extended Russia-Ukraine war or in its aftermath. North Korea’s decision to build a Memorial Museum of Combat Feats dedicated to its soldiers who fought in Kursk only reinforces this assessment.

Assessing North Korea’s intentions toward Russia requires looking beyond the immediate economic, diplomatic, and military-technology benefits Pyongyang has reportedly been reaping from this burgeoning relationship. We should also consider the perceived opportunities from Kim’s point of view. These may include diversifying economic and trade partnerships through Russia or gaining access to multilateral diplomatic platforms. For example, North Korea has strengthened ties with Belarus, a key Russian ally, since 2024. Its foreign minister has also participated in Russian-influenced forums, including the BRICS Women’s Forum in 2024 and the Third Minsk International Conference on Eurasian Security in 2025.

Pyongyang-Beijing Ties: On a Path Toward Recovery

North Korea-China relations enjoyed a new heyday following Kim’s five summits with Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2018 and 2019. However, the North’s invitation of Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu to the Armistice Day celebrations in July 2023 – an event North Korea has historically observed with China – appeared to be a subtle message to Beijing that it was reconsidering its policy priorities. By the fall of 2023, this shift had become evident. North Korea’s behavior toward China became noticeably cooler. Its official readout of Kim’s meeting with a Chinese delegation to the North’s founding day celebrations in September, as well as Kim’s letter to Xi Jinping on China’s founding day, were both subdued. The reasons for this shift are unclear, but its timing aligns with deepening North Korea-Russia ties, of which Shoigu’s July visit was a milestone.

Signs of strained relations persisted in 2024, despite it being the 75th anniversary of diplomatic ties between North Korea and China. Exchanges between the two countries remained limited and low-level, with only one high-level Chinese delegation visiting Pyongyang in April. By July 2025, North Korean media showed signs of improving relations with China, marked by an increase in diplomatic events and higher-level North Korean officials attending Chinese embassy-hosted functions compared to 2024.

Kim’s summit with Xi on the sidelines of China’s “Victory Day” celebrations in September – his first in more than six years – was the first step toward restoring frayed ties. North Korean media’s official report of the summit included some positive references, such as the two leaders’ commitment to developing relations “no matter how the international situation may change,” increasing “high-level visits and strategic communication,” and strengthening “strategic cooperation and defending common interests in international and regional affairs.” Breaking from past summit reports, this readout even cited Kim’s support for China’s “sovereignty” and “territorial integrity,” a veiled reference to Taiwan. However, it lacked alignment language found in coverage of past Kim-Xi summits, such as “shared understanding,” “unanimously agreed,” or “reached a consensus.”

Kim’s letters to foreign counterparts are reliable gauges of North Korea’s relations with those countries, since any public communications attributed to Kim carry the highest authority in North Korea. In this context, Kim’s two letters to Xi following their September talks – his reply to Xi’s congratulatory message on North Korea’s founding day and his letter on China’s founding anniversary (October 1) – merit closer study. Both letters were more positive than Kim’s 2024 messages to Xi on the same occasions, when the relationship was at a low point. For example, Kim’s 2025 reply acknowledged China’s “invariable support” for North Korea, stock language absent from his 2024 reply. His October 2025 letter said he “has a willingness to make … efforts” to “defend peace and stability in the region and the rest of the world,” also absent from the 2024 message. On the whole, however, both messages remained cooler than Kim’s letters to Xi from 2018 until 2023, when relations were stronger.

North Korean media coverage of the October talks between North Korean Premier Pak Thae Song and the visiting Chinese Premier Li Qiang showed further progress. The coverage cited Pak’s support for China’s “core interests including the Taiwan issue” and quoted his remark that North Korea “would oppose hegemony and jointly defend fair international order and peace with the Chinese comrades.” Both formulations were more specific than the language attributed to Kim in the summit readout.

Notably, however, North Korea continues to avoid attributing alignment language to Kim himself. In sum, bilateral relations appear to be improving but are not fully restored. How far the relationship will heal requires further analysis of future developments.

Conclusion

North Korea’s expanded relations with Russia give Pyongyang greater flexibility and leverage, including in its ties with China. The future of North Korea-China relations will therefore be affected by Pyongyang’s relations with Moscow. In this context, despite efforts to rebuild ties with China, North Korea appears to prioritize Russia. This was evident during the WPK founding anniversary celebrations in October: although China sent a higher-level delegation to Pyongyang, Kim Jong Un devoted more time to Russian visitors, skipping a Chinese performance but attending a Russian one, both held on the anniversary’s eve. The Ninth Party Congress, likely to be held in early 2026, will unveil North Korea’s foreign policy direction for the next five years and offer more clarity into the leadership’s calculations.