From Amazon to the Third Pole: Why COP30 and BRICS Must Elevate Tibet’s Climate Emergency

November 14, 2025: The Stockholm Center for South Asian and Indo-Pacific Affairs (SCSA-IPA) at the Institute for Security and Development Policy (ISDP) undertook a strategic undertaking to Brazil during COP30 in Belém, followed by high-level dialogues in Rio de Janeiro, to highlight one of the world’s most neglected ecological flashpoints: the accelerating climate crisis across Tibet and the Himalayan region. This visit formed part of the Center’s flagship project, “Whither Tibet in Climate Crisis Agenda,” a striking conversation at the COP30, culminating in the release of the report in Rio and exchanges with the Brazilian knowledge community, experts, and policymakers.

The delegation, led by Dr. Jagannath Panda, Head of SCSA-IPA, and joined by Mr. Richard Ghiasy, Senior Associate Fellow at SCSA-IPA and Director of GeoStrat (The Netherlands), participated in COP30 as observers and interlocutors focused on expanding global awareness of high-altitude climate vulnerabilities. Their message was unequivocal: the Tibetan Plateau, Asia’s “Third Pole”, is undergoing an ecological breakdown that global climate governance can no longer afford to ignore.

Tibet’s Melting Crisis in the Shadow of COP30’s Amazon Focus

COP30’s central themes of Amazonian preservation, Indigenous environmental rights, and sustainable development have rightly captured global attention. Yet, the SCSA-IPA team noted that another ecosystem of planetary significance, Tibet, remains conspicuously underrepresented in international climate discourse. The Tibetan Plateau is warming nearly three times faster than the rest of the world, triggering rapid glacial retreat, permafrost degradation, and destabilisation of major river systems.

In meetings with climatologists, Indigenous rights specialists, and environmental researchers in Belém, Dr. Panda emphasised that the consequences of Tibet’s environmental deterioration extend far beyond China’s borders. The Tibetan Plateau feeds ten major river systems, sustaining nearly 2 billion people across South Asia and Southeast Asia. The loss of ice reserves shifts in precipitation patterns, and intensifying water scarcity downstream could reshape the region’s food security, energy planning, disaster vulnerability, and geopolitical dynamics.

The crisis is compounded by Beijing’s expanding hydro-infrastructure, including dams and diversion schemes along major transboundary rivers. The newly proposed Medog Water Diversion Project stands out as an initiative with profound implications for downstream countries, one that could alter the ecological balance of the Brahmaputra basin and aggravate regional insecurities.

Mining pressures add another dimension to the ecological threat. Rising extraction of lithium, rare earths, copper, and other resources across Tibet has disrupted fragile mountain terrains and contributed to soil degradation and habitat loss. Simultaneously, the forced relocation of Tibetan nomadic communities has weakened long-established systems of high-altitude environmental stewardship. According to Dr. Panda, climate justice cannot be meaningfully pursued if the world’s largest freshwater reserves outside the polar regions continue to disappear without scrutiny or accountability. Some of these issues were shared in the international media outlets such as CNN Brazil and CNBC Brazil.

ISDP–CEBRI Dialogues: Bringing Tibet into BRICS and UNFCCC Climate Frameworks

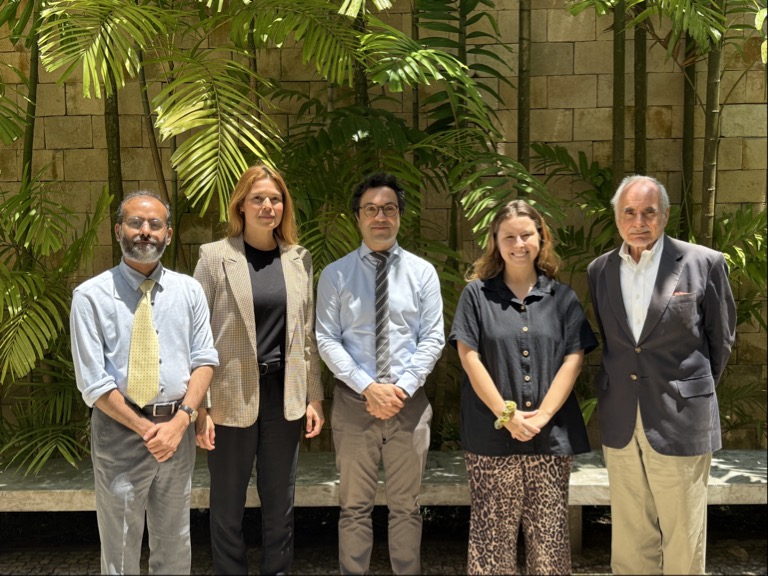

In Rio de Janeiro, the SCSA-IPA released its “Whither Tibet in Climate Crisis Agenda” report during an in-depth interaction hosted by the Brazilian Center for International Relations (CEBRI), an influential think-tank. Senior Brazilian representatives, including Ambassador Antonio de Souza e Silva, Isabella Ávila, Claudia Lundgren, and Alice Nascimento, engaged with ISDP on the strategic and ecological implications of climate deterioration globally, including in Tibet.

The interaction produced a strong, shared conclusion: BRICS and UNFCCC must engage Tibet as a climate governance priority rather than a politically sensitive issue tied to China’s internal considerations. Both sides, SCSA-IPA and CEBRI, agreed that the climate agenda of BRICS, particularly its focus on sustainable development, environmental cooperation, and South–South linkages, cannot remain complete if high-altitude ecosystems continue to be sidelined. The BRICS platform, they noted, is uniquely positioned to promote atmospheric monitoring, glacial studies, hydrological transparency, and shared adaptation frameworks for Asia’s river basins.

A major outcome of the discussion was the recognition that climate governance obligations such as hydrological data sharing, early warning systems, and transboundary river monitoring must become universal responsibilities, not politicised concessions. Tibet’s glaciers, rivers, and landscapes constitute a global ecological commons; thus, their depletion demands multilateral oversight and the collective effort of scientific engagement.

The dialogue drew an especially powerful parallel between the forced relocation of Indigenous communities in the Amazon and the displacement of Tibetan nomads from their ancestral lands. In both cases, communities with long-standing ecological knowledge, essential for sustaining fragile ecosystems, are being marginalised. Such displacement accelerates environmental vulnerability by undermining local conservation practices and reducing cultural resilience.

By juxtaposing these experiences, the ISDP-CEBRI exchange deepened Brazil’s understanding of the Tibetan crisis, linking the Himalayan melt to broader global debates on Indigenous rights, environmental justice, and climate governance. As part of its Brazil outreach, the ISDP delegation also visited PUC-Rio, one of Latin America’s leading academic institutions.

Strengthening South–South Climate Conversations

During the visit to Brazil to attend the COP 30, the ISDP team focused on connecting scientific research on Amazonian degradation with parallel environmental disruptions in the Himalayan region. Many climatologists and experts at the COP30 underscored that while the Amazon faces threats from deforestation, land-use change, and extractive industries, Tibet confronts glacial loss, water scarcity, habitat disturbance, and mining-related stress, yet both ecosystems share a key vulnerability: the erosion of Indigenous and local stewardship systems.

The discussion highlighted that climate change in high-altitude regions receives significantly less global funding and scientific attention compared to rainforests or coastal zones, despite their equal influence over global hydrological cycles. Scholars and experts noted that integrating Tibetan concerns into South–South climate cooperation, especially through BRICS, would help diversify global understanding of climate hotspots and encourage shared research on hydrology, biodiversity, and environmental governance. Brazil’s position as COP30 host, combined with its leadership in Amazon conservation, makes it a crucial voice for expanding the global climate agenda to include lesser-recognised but equally critical ecosystems such as the Tibetan Plateau.

A Call for a Broader Climate Horizon

As COP30 shapes the contours of global climate action and Brazil shepherds debates around sustainability and equity, the SCSA-IPA mission underscores a vital message: the world cannot safeguard the climate future without confronting the ecological breakdown of the Himalayan and Tibetan regions. The Third Pole’s destabilisation is not an isolated phenomenon; it is a systemic threat that will shape Asia’s water security, regional stability, and climate resilience for decades to come. The “Whither Tibet in Climate Crisis Agenda” report released in Brazil sends an unmistakable signal: “The global climate agenda– from the Amazon to the Indo-Pacific– must recognise Tibet as a core pillar of planetary environmental health.”