Elimination of Tropical Diseases: Strengthening Collective Action in a Fragmented World

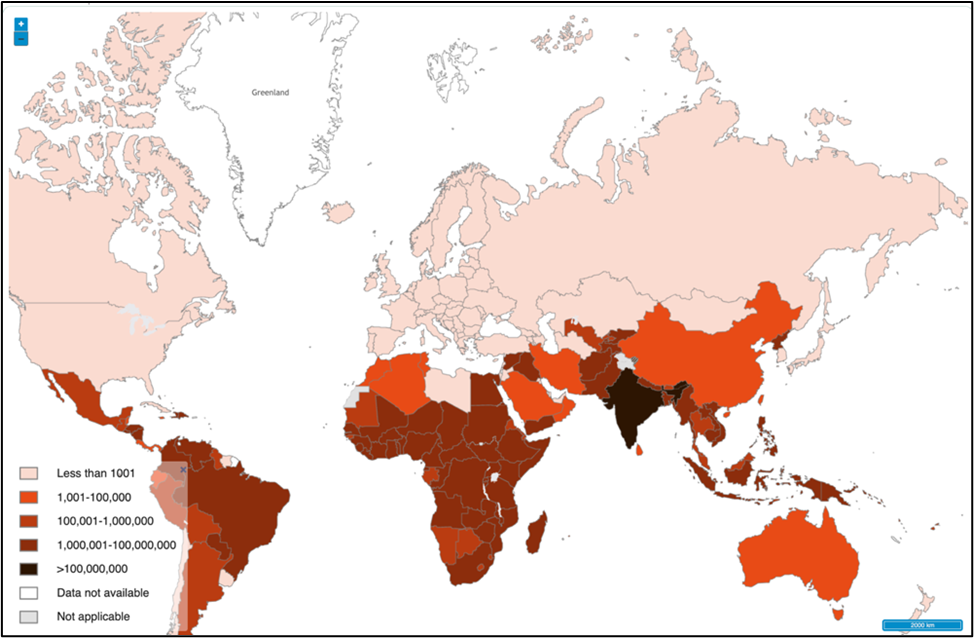

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) remain a major global health challenge, affecting more than one billion people worldwide. NTDs cause chronic pain, visible disfigurement, disability, stigma, and long-term economic exclusion, primarily among populations already facing poverty, weak health systems, and climate vulnerability. Households lose an estimated USD 33 billion each year due to NTD-related health costs and lost productivity. Despite the fact that prevention and elimination interventions are among the most cost-effective investments in global public health. Progress on NTDs, however, has been uneven, and varied sharply across regions between 1990 and 2021. Southeast Asia recorded major improvements, with age-standardized prevalence falling by 80.7 percent, while Andean Latin America moved in the opposite direction, with prevalence increasing over the same period. NTDs like intestinal nematode infections and leishmaniasis, declined substantially, while schistosomiasis, dengue, and cysticercosis rose in prominence within overall disease burden rankings.

NTDs are no longer only a development or health-sector concern. They increasingly constitute an international policy issue. Climate change, population mobility, and rapid urbanization are reshaping transmission patterns, expanding vector habitats, and introducing NTD risks into new geographies. The spread of NTDs into Europe and growing concern in high-income countries illustrate that these diseases are no longer geographically contained. As a result, NTD elimination intersects with global health security, climate resilience, and development, making it a shared international responsibility rather than a purely national one. In 2021, the World Health Assembly formally recognised January 30 as World NTD Day, signalling collective political acknowledgement that NTDs undermine health systems, development trajectories, and long-term security. The theme of this year’s World NTD Day is “Unite. Act. Eliminate.”, reflecting this transition. With the World Health Organization (WHO) committed to a 90 percent reduction in the number of people requiring interventions for NTDs by 2030 (see Figure 1), the remaining challenge is no longer about technical feasibility, but requires political and institutional follow-through.

Figure 1: Reduction in the number of people requiring interventions for neglected tropical diseases (WHO 2030 target).

Source: WHO NTD Roadmap Tracker (2021–2030).

Existing Global Solutions

Effective solutions to prevent, control, and eliminate NTDs already exist. Over the past four decades, mass drug administration (MDA), strengthened surveillance, vector control, water and sanitation interventions, and community-based delivery platforms have demonstrated substantial impact. These approaches are consolidated in the WHO NTD Roadmap 2021–2030, which sets clear, measurable targets and emphasises country ownership, integration, and accountability. Global progress has also been enabled by long-standing partnerships across stakeholders such as governments, industry, civil society, and research institutions. Pharmaceutical donations and coordinated delivery models have made it possible to reach millions of people at risk, while global targets have provided a shared direction for action. In short, the policy tools for elimination are proven and available.

Strengths and Persistent Gaps: Lessons from Practice

Recent examples illustrate how NTD elimination has evolved from reliance on pharmaceutical donations toward domestic resource mobilization. A defining strength of the global NTD response has been the availability of effective tools at scale. The modern global response to NTDs was catalysed in 1987, when Merck & Co. announced it would donate Ivermectin for as long as needed to treat Onchocerciasis. This unprecedented commitment enabled mass drug administration (MDA) to emerge as a scalable elimination strategy. The success of Ivermectin distribution triggered further pharmaceutical donations and laid the foundation for new global partnerships. This momentum culminated in the London Declaration on NTDs in 2012, where endemic countries, donors, industry, and civil society committed to accelerating elimination. Importantly, subsequent progress reports marked a shift away from external generosity toward domestic responsibility. Endemic countries were increasingly called upon to scale programs, reach all populations at risk, and invest domestic resources. The lesson is clear: partnerships and donation can unlock progress, but elimination ultimately depends on sustained political commitment and institutional ownership by states.

Tanzania exemplifies the implementation of elimination-target governance. When external funding was suspended in 2025, the Ministry of Health moved quickly to mobilise domestic resources, reallocating funds through Comprehensive Council Health Plans and the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework. In 2025–26, all 184 districts set aside funding for NTD programs. These outcomes were the result of deliberate political choices. By integrating MDA into routine services such as immunization and vitamin A supplementation, and by relying on community health workers to deliver treatment at lower cost, Tanzania maintained momentum. Trachoma-endemic councils fell from 69 in 2012 to seven in 2024, while lymphatic filariasis declined from 119 councils in 2015 to five by 2024. Tanzania’s experience shows that domestic resource mobilisation is not just technical, it reflects commitment to equity, even in the face of uncertainty. Together, these cases reveal a central paradox. The global NTD response is strong on solutions, yet uneven in outcomes. Where governance is fragmented or heavily donor-dependent, progress remains fragile. And where elimination is institutionalised, gains are more likely to endure.

Solutions Through International Cooperation

Because NTD elimination generates cross-border benefits, it should be treated as a global public good. International cooperation is therefore essential not as a substitute for domestic responsibility, but as a mechanism to reinforce it. Multilateral platforms play a critical role in sustaining political visibility, aligning financing with global targets, and supporting countries transitioning toward greater domestic ownership. International cooperation must also be cross-sectoral. Health departments alone cannot address the environmental, social, and infrastructural drivers of NTDs. Collaboration across climate, water and sanitation, education, and urban planning sectors is essential for sustainable elimination. Without such coordination, technical gains risk being reversed by environmental change or system shocks. India offers an example based on cross-sectoral collaboration. The Prime Minister’s Science, Technology, and Innovation Advisory Council (PM-STIAC) approved the establishment of a National One Health Mission. The mission is designed as a cross-ministerial effort. It will coordinate, support, and integrate existing One Health initiatives across the country, while addressing critical gaps where needed.

Organisations Supporting Elimination Efforts

A diverse set of actors continues to support NTD elimination. For instances, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation promotes actionable policy solutions via public–private partnerships and diplomatic advocacy for accessibility. Pfizer reinforced its antibiotic donation initiative by extending it till 2030. Ghana has institutionalized elimination through national health staff funding, NTD commodity regulation exemptions, and multisectoral coordination platforms. The Drugs for Neglected Diseases program enhances the policy framework by promoting patient centric research while garnering political support for a more equitable innovation system. Collectively, these endeavours show that the policy and technical elements for elimination are already in place. What varies across contexts is the degree of coordination, institutionalisation, and political prioritization.

The Policy Window: Applying a Governance Framework

World NTD Day 2026 should be treated as a governance deadline, not a symbolic commemoration. A clear policy window has opened, shaped by lessons from the COVID-19 crisis and a growing recognition that NTDs are part of the global health security agenda, particularly in the context of climate change and rapid urbanization. In 2023, around 1.5 billion people still required NTD interventions, but this marked a 32 percent reduction from 2010. Disease burden and deaths continue to decline, and nearly 867 million people were treated in 2023, most through preventive chemotherapy. Yet reaching the WHO 2030 roadmap targets will require more than sustaining current approaches. Strategic use of artificial intelligence and digital health can accelerate progress by improving diagnosis, strengthening surveillance, and enabling real-time follow-up in fragile settings. With fewer than five years remaining, there is a need to strengthen governance frameworks that can integrate these tools into routine, accountable NTD programmes.

Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework offers a practical guide for converting existing momentum into durable policy change. The problem is visible, the policy tools are proven, and political attention is present but fragile. What is required now is deliberate alignment. First, the problem stream must remain visible. Governments and international partners should continue to frame NTDs as diseases of equity, and climate risk, while using national data reporting to keep the burden politically salient. Transparency through global tracking tools can prevent NTDs from slipping back into neglect. Second, the policy stream must be institutionalized. Interventions such as MDA, integrated surveillance, and community delivery should be embedded within routine health systems rather than treated as time-limited projects. Evidence-to-policy mechanisms should be formalized within ministries/departments of health. Third, political commitment should be translated into health financing mechanisms, national polices as well as cross-sector mandates that survive electoral cycles and donor volatility. Domestic resource mobilization, as demonstrated by Tanzania and Ghana, should be recognized and rewarded by international partners. When these streams are deliberately aligned, elimination-target governance becomes durable. When they are not, progress remains fragile and reversible.

Choosing Elimination

Eradicating NTDs is achievable. Effective medicines exist, interventions are proven, and global manufacturing capacity, resilient supply chains, and a trained health workforce anchored in good governance are the enablers of scale and continuity. Leaders must now institutionalize elimination as a core public obligation, shaping not only the future of NTDs but also the credibility of global health commitments in an increasingly fragmented world.