Corridors of Culture, Routes of Power: CPEC in Xi’s GCI

After almost three years on hold, the foreign ministers of China and Pakistan recently announced plans to advance construction of the upgraded China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), agreeing to broaden collaboration in industry, agriculture, mining, and green energy. The question that arises is whether China is exporting infrastructure or a worldview? As Beijing speaks the language of civilizational respect and mutual learning, its roads, ports, and pipelines continue to reshape South Asia’s political economy. At the heart of this paradox sits Xi Jinping’s Global Civilization Initiative (GCI), which asserts a commitment to dialogue over dominance, operating in tandem with the hard steel and soft loans of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Nowhere is this convergence more visible, or more strategically significant, than in South Asia, and especially in Pakistan through the CPEC.

The debate, then, is no longer whether China is building influence through connectivity. The deeper question is whether Beijing is using civilizational discourse to reframe power itself. Is GCI a genuine attempt to pluralize global norms, or a strategic narrative designed to legitimize BRI’s expansion in contested regions? Why does Pakistan occupy such a central place in this experiment? And how does the renewed political and financial push behind CPEC’s second phase and the development of Gwadar fit into China’s broader South Asian strategy?

GCI as the Cultural Architecture of BRI in South Asia

The GCI positions itself as a rejection of civilizational hierarchy and ideological universalism. Its core claim that no single civilization has the right to define modernity resonates deeply in South Asia, a region shaped by colonial legacies and post-Westphalian anxieties. By advancing the language of civilizational equality, China offers an alternative narrative to Western-led development and governance frameworks.

In practice, however, GCI does not operate in isolation. It functions as the normative layer of BRI, giving cultural and philosophical coherence to what is otherwise a sprawling infrastructure project. At the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing in May 2017, Xi Jinping gave an impassioned speech about the lofty aims of the BRI, stressing the need to “build the BRI into a road of civilisation.” From there, the leap to GCI has been swift. In South Asia, where geopolitical mistrust of China remains high, GCI helps soften BRI’s image by reframing connectivity as dialogue and development as mutual learning (相互学习). This is particularly effective in countries that feel marginalized by Western financial institutions or fatigued by conditional aid regimes. South Asia thus becomes a testing ground for China’s claim that infrastructure-led growth can coexist with civilizational pluralism. Roads and ports are no longer presented merely as economic assets, but as conduits of historical exchange—revived Silk Routes linking civilizations rather than states.

Pakistan and CPEC: The Civilizational Anchor

Within this regional strategy, Pakistan occupies a privileged position. China’s rhetoric increasingly presents Pakistan not just as an “iron brother,” but as a civilizational partner—an Islamic, South Asian state that validates Beijing’s argument that modernization need not follow a Western script. CPEC, in this sense, is framed as a corridor of shared destiny rather than a bilateral bargain, extending its strategic proximity even to the Indian Ocean Region countries, such as the Maldives.

This framing is politically useful. As CPEC has come under scrutiny for debt exposure, security vulnerabilities, and uneven development, GCI provides a narrative shield. By embedding CPEC within a civilizational discourse, Beijing shifts attention away from transactional concerns toward long-term partnership and shared historical identity. The emphasis on people-to-people exchanges, educational cooperation, media collaboration, and cultural diplomacy under CPEC is not incidental; it operationalizes GCI’s promise of mutual learning.

In turn, Pakistan has gained from infrastructure modernization. By 2023, infrastructure investments resulted in contributing more than 8,000 MW to the national energy grid and boosting exports to China by 46%. However, a widening trade deficit alongside increasing fiscal dependence and rising domestic discontent in regions such as Balochistan and Gilgit-Baltistan underscores the complex and uneven nature of this interdependence.

Pakistan’s domestic power structure further reinforces the situation. GCI-linked engagement under CPEC is largely elite-driven, working through political leadership, the military, and bureaucratic institutions. This top-down model ensures policy continuity even amid Pakistan’s internal instability, making the country an ideal anchor for China’s civilizational outreach in South Asia.

CPEC Phase II and Gwadar: Finance, Politics, and Strategic Narrative

China’s renewed political and financial backing for CPEC Phase II signals a pivotal shift and the complexities of their interdependencies. The emphasis has moved from headline infrastructure to industrial cooperation, special economic zones, agriculture, and technology. This transition is not merely economic and reflects Beijing’s determination to demonstrate that BRI corridors can mature into sustainable eco-systems.

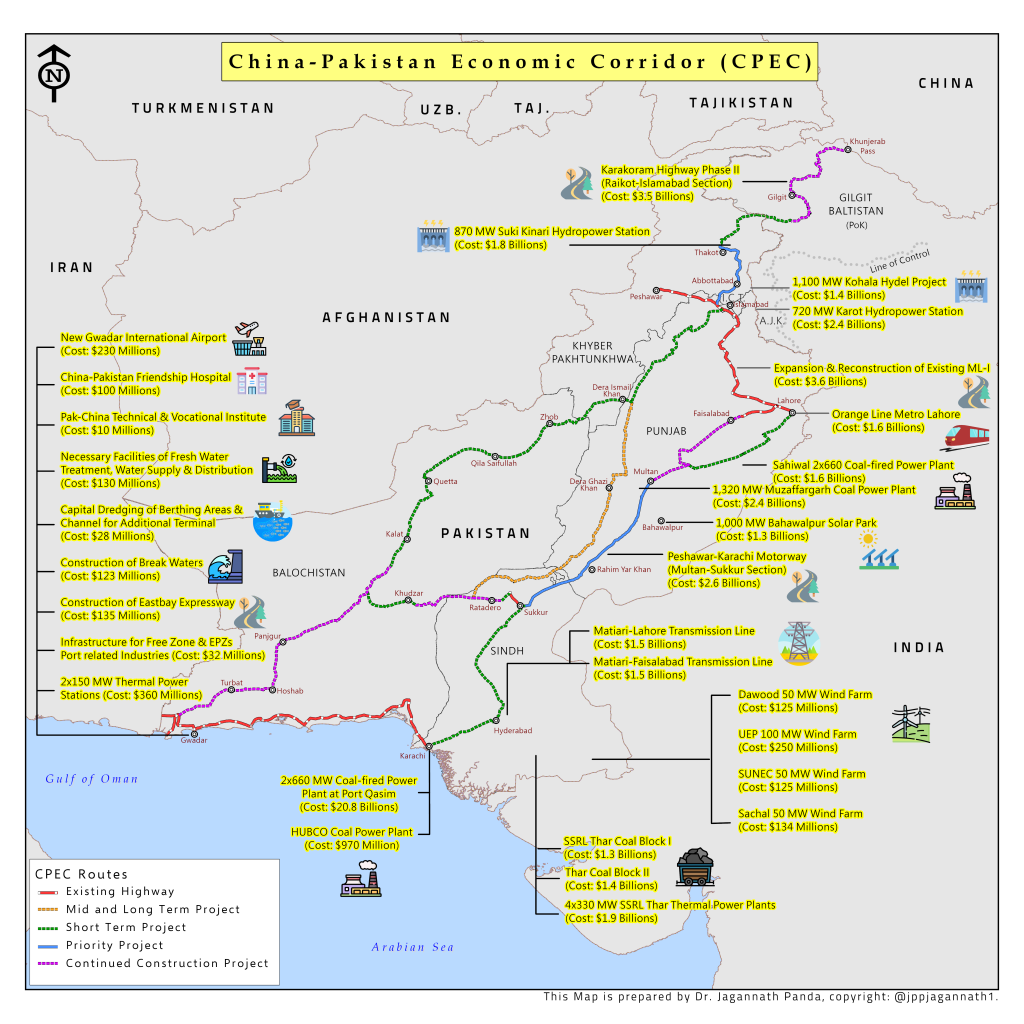

The CPEC, stretching about 3,000 km from Xinjiang in northwestern China to Gwadar port (瓜达尔港) on the Arabian Sea (see map), constitutes a central component of the BRI with total investments said to be exceeding $60 billion. In Phase II of the project, the two countries have committed to collaboratively establishing corridors for economic growth, social development, innovation, green development, and openness to deliver an enhanced version of CPEC consistent with Pakistan’s development plans. Pakistan’s location, a mere 600 kilometres from the Strait of Hormuz, gives it unparalleled strategic importance. Far from being solely an economic project, CPEC functions as a strategic lifeline intended to expand China’s regional footprint and protect its enduring energy and commercial interests.

Gwadar, once a sleepy fishing village, sits at the center of this ambition. Back in 2015, Xi Jinping elevated CPEC to the highest priority and described it as the “flagship” of the BRI. Xi then named Gwadar as one of the four pillars of CPEC. The commercial and potential military significance of Gwadar is best understood through the concept of China’s “strategic strongpoints,” a term referring to select foreign ports of high strategic importance where terminals and commercial zones are operated by Chinese companies. Undoubtedly, the development of the Gwadar port strengthens China’s maritime footprint presence in the Indian Ocean, raising concerns about potential strategic encirclement.

But, of late, it is more than a port; Gwadar is being projected as a symbol of connectivity between inland China, South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Under the GCI lens, Gwadar is framed as a civilizational gateway, reviving maritime Silk Road traditions while anchoring China’s presence in the Indian Ocean. Continued Chinese financing, concessional loans, and political support for Gwadar indicate that Beijing views the port as both a strategic asset and a narrative showcase. Crucially, this support persists despite security challenges and economic headwinds. That persistence underscores a key point: CPEC is no longer judged solely by immediate returns. It is valued as a long-term experiment in integrating civilizational discourse with strategic infrastructure—an experiment China is unwilling to abandon.

Power, Pluralism, and the South Asian Question

What emerges from this convergence of GCI, BRI, and CPEC is a distinct Chinese approach to regional order-building that differs from the Western tradition of exporting institutions, norms, or governance frameworks. Rather than foregrounding universal legal standards or multilateral institutions, Beijing’s approach emphasizes connectivity as a core organizing principle, one embedded in economic interdependence, infrastructure linkage, and cultural-diplomatic narratives.

South Asia, with Pakistan at its core, becomes the proving ground for whether this model can gain legitimacy amid rivalry, resistance, and regional asymmetries. Yet the debate remains unresolved. Can the rhetoric of shared civilization and collective development truly neutralize concerns about strategic dependency akin to a silken cage? Does framing infrastructure as dialogue meaningfully empower local societies, or does it consolidate elite alignments? Studies on CPEC and its regional effects highlight how deepening connectivity can simultaneously foster interdependence and geopolitical competition, raising questions about sovereignty and regional asymmetries. And as CPEC deepens under Phase II, will Pakistan’s experience become a model others emulate or a cautionary tale?

These questions cut to the heart of China’s global ambition. GCI’s success in South Asia will depend not on speeches or symbolism, but on whether connectivity delivers stability and sustainable development without eroding sovereignty. For now, Pakistan and CPEC stand as the clearest expression of China’s wager: that culture can legitimize power, and that corridors, both physical and civilizational, can redraw the map of influence in the 21st century.

This piece is a part of Stockholm Center for South Asian and Indo-Pacific Affairs’ (SCSA-IPA) research project, “The Silk Noose: China’s Power Architecture in South Asia and the Indian Ocean Region”.